I’ve just finished my first week at my new job. Well, technically I was at work, but actually, I was at a training event for the Sales team. Except for when I was at IBM, I don’t think I’ve ever started a job and been provided with a proper orientation to the company. Until now.

It was just my luck that I would start a new job at the same time as the entire company came together for its annual meeting. Wow. Wow. Wow. When you say the word three times quickly, it loses its meaning; so consider how blown away I must have been for the word to have retained its meaning over the week. These guys are serious. These guys have a plan. These guys are going to get *bleep* done.

It was just my luck that I would start a new job at the same time as the entire company came together for its annual meeting. Wow. Wow. Wow. When you say the word three times quickly, it loses its meaning; so consider how blown away I must have been for the word to have retained its meaning over the week. These guys are serious. These guys have a plan. These guys are going to get *bleep* done.

Behind the superficial organization of pretty corporate branding lay a much deeper organization. Most technology startups (or at least the ones I’ve been a part of) have an annoying tendency to try to do everything; they see all the possibilities of the technology, and fail to focus. Not a problem here.

By far the most impressive feature of the week of training was not what the company was going to do, but the forcefulness with which it had decided not to do certain things. That may not sound very intelligent to an outsider (“Excuse me, but don’t companies only make money if they actually do something?”), but when you’ve been on the inside of the “what’s the product this week” machine, you appreciate it. It shows focus.

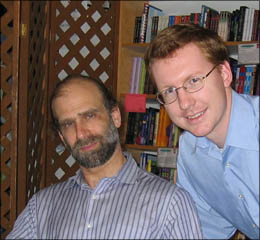

Meanwhile, in other exciting things – I met Bruce Schneier at his book-signing at Kepler‘s book store. Let the hero-worship begin!