I’ve been a longtime Google Reader user, and I recently decided to explore their “Shared items” capability. The idea of “Shared items” is that you can mark posts interest you come across in Google Reader, and share them with your friends; and, vice-versa, you can view items your friends have shared with you. Pick the right friends, and your social network becomes an effective news filter, minimizing the amount of RSS feeds you actually track and read.

It sounds like a great idea, until you try to use the feature. The first step in any social networking-type application is simple: add your friends. If you got no friends, the whole thing doesn’t work. It would seem reasonable, therefore, that the first and most important aspect of such an application would be to make adding friends easy. It is in this regard that Google Reader not only hops on the failcopter, but grabs control of the stick, and jams it into a steep descent. Into the side of a mountain.

To add friends in Google Reader, you have to add friends in…GTalk? It’s hardly an auspicious start to the user experience when using the web application requires the user to navigate to another web application. And of course, to use GTalk, you have to use Gmail. Fine, whatever, I already use Gmail. In fact, I’ve imported about 1000 contacts into my Gmail address book, so the rest should be simple, right?

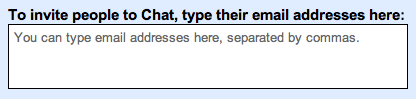

Wrong. Here’s the UI to add a user to GTalk:

That’s right, you have to add users manually. In addition, there’s no autocomplete capability either, which means you’ll have to type in all of your friends’ complete email addresses. Who thought this was a good idea? It’s like the application needs human suffering to provide sustenance. Does this application thrive on misery?

Seriously, Google, come on. I’ve given you my email contacts. You even have a Google Contacts API that allows third parties to use my Gmail contacts! What the heck is going on here? In fact, this UI shouldn’t even exist – it should be a list of my Gmail contacts, filtered by those that are already using GTalk, that allows me to easy select a number of contacts and make the request. Done.

The lack of integration between different web properties is not unique to Google. If you use Upcoming, you’ll note that adding a user is a painful manual process similar to the Google Reader experience.

It’s like they actually want these applications to fail. If these providers can’t even integrate their own APIs to simplify the exchange of data within their own company, what hope does the DataPortability movement have?